|

THE BALANCING WELL IN FRANCE

Christian Lassure

French version

1 - THE SWEEP FOR DRAWING WATER: AN OVERVIEW

The sweep (or swipe) for drawing water is an ingenious elevating device using a first-order lever turning in its middle about a pivot and carrying a vessel at one end and a counterweight at the other. A slight variation of the weight on one of the two arms of the lever is sufficient to set the latter rocking. Erected over a well, cistern, pond, or water stream, this lifting apparatus turns into child's play what would otherwise be a tiresome job. A well-known instance of sweep is the Egyptian shadouf.

Already extant in Antiquity and common in the Middle Ages, the technique is, or used to be, widespread from France to Japan. It is, or was, found not only in the Far East, Western Africa, North Africa, but also throughout Europe.

The device goes under the names of cegonha in Portugal, mezzacavallo in Italy, brunnenschwegel in Germany, vippebronden in Denmark, kutostor in Hungary, cumpana in Romania.

In France alone, in 1986, there remained a few surviving examples of well sweeps in as many as 36 départements (*). In 2021, the number of départments where sweeps still exist or are known to have existed in the past is 47.

where they are known, according to regional dialects, as cigogne / cigounho, canlèvo, banlèvo, manlèvo, gruo, brimbale. This last designation, originating in Charente, migrated across the Atlantic to French-speaking Quebec together with the device.

|

|

|

47 départements : 01 = Ain - 04 = Alpes-de-Haute-Provence - 06 = Alpes-Maritimes - 07 = Ardèche - 09 = Ariège - 10 = Aube - 12 = Aveyron - 13 = Bouches-du-Rhône - 15 = Cantal - 16 = Charente - 17 = Charente-Maritime - 18 = Cher - 19 = Corrèze - 21 = Côte-d'Or - 22 = Côtes-d'Armor - 23 = Creuse - 24 = Dordogne - 25 = Doubs - 29 = Finistère - 31 = Haute-Garonne - 32 = Gers - 33 = Gironde - 37 = Indre-et-Loire - 38 = Isère - 39 = Jura - 40 = Landes - 41 = Loir-et-Cher - 45 = Loiret - 46 = Lot - 47 = Lot-et-Garonne - 48 = Lozère - 49 = Maine-et-Loire - 52 = Haute-Marne - 54 = Meurthe-et-Moselle - 57 = Moselle - 63 = Puy-de-Dôme - 64 = Pyrénées-Atlantiques - 65 = Hautes-Pyrénées - 67 = Bas-Rhin - 68 = Haut-Rhin - 71 = Saône-et-Loire - 79 = Deux-Sèvres - 82 = Tarn-et-Garonne - 85 = Vendée - 86 = Vienne - 87 = Haute-Vienne - 90 = Territoire-de-Belfort. |

The sweep for drawing up water, as encountered in Europe, consists of four elements:

1 - a fixed vertical element (the support or upright), generally either a tree trunk topped by a fork, or a post ending with a fork-like mortise or pierced at the top by a through mortise, or sometimes twin posts ; it acts as a pivot or fulcrum ;

2 - a rotating horizontal element, i.e. a metal or wooden axis running through the fork or the fork-like mortise or the through mortise ; it enables the sweep to swivel ;

3 - a mobile horizontal element (the beam or sweep proper), consisting of a long tapered rod resting on the upright ; to its thinner arm – the load arm or jib – on the water's side, the hanging system is fastened ; to its thicker arm – the force arm or tail – on the opposite side, a counterweight is fastened ;

4 - an articulated hanging element, a wooden bar or an iron rod fastened to the jib's end by a short upper chain and prolonged by a long lower chain with a hook.

Because of the counterweight weighting its tail arm, the beam, when at stanstill, tilts to the side opposite the water, resting either on the ground or in a fork, or again on a trestle.

In practice, it is necessary for the bar to be pulled down in order to lower the jib arm and sink the vessel into the water. But once the vessel is filled, the two arms of the beam come into balance again, and it only takes a slight pull upwards to initiate a rocking movement that will lift the water-filled bucket.

While the pulley is employed in connection with deep aquifers, the use of the sweep is confined to shallow water-tables and, naturally, water streams. Several sweeps can be placed in successive levels to raise water to the required level, as in Egypt, on the Nile banks, or they can be operated side by side, on the same level, to achieve continuous irrigation, as in the Sahara oases.

In the European rural environment, the sweep for raising water is likely to have been built by:

- an individual farmer, either on a river bank to irrigate a kitchen garden or a cultivated field, or in a farmyard to draw rain water from a cistern ;

- a small community on communal land inside a hamlet or a village, to provide drinking water to people and cattle or to supply a wash-house ;

- a craftsman, such as a brickmaker, to collect the water necessary to mold clay bricks or tiles.

Today, the tall silhouette of the machine is gradually being obliterated from the rural landscape by technological progress (in the form of mains water supply and pumps).

(*) Not including Territoire de Belfort, where a few specimens are still extant today, and Meurthe-et-Moselle and Alpes-Maritimes, two départements in which early-twentieth century postcards bear out the existence of the device.

Bibliography

Henri Polge, Typologie du cigognier, in Documents et archives pour la recherche sociolinguistique méridionale, 1976, No 1, pp. 18-23.

Christian Lassure, Une vieille technique de puisage en perdition : le balancier à tirer l'eau, Etudes et recherches d'architecture vernaculaire, No 6, 1986, 40 p.

Christian Lassure et François Véber, Le puits à balancier communal de Fonniovas à Sorges (Dordogne). Etude ethno-archéologique, in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 10, 1986, pp. 27-32.

Christian Lassure, Sur quelques constructions à pauxfourches, balanciers de puits et bâtiments de type halle dans le nord-est de la Dordogne, in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 13, 1989, pp. 81-86.

Serge Avrilleau, Christian Lassure et François Véber, Elévateurs à balancier d'Adoux-bas et d'Adoux-haut à Sarliac (Dordogne), in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 13, 1989, pp. 89-92.

Christian Lassure, rubrique Well-sweep, dans Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, edited by Paul Oliver, Cambridge University Press, 1997, vol. 1, VI, Services, p. 494.

Michel Rouvière, Sur quelques systèmes hydrauliques en Ardèche méridionale, in L'eau en Ardèche. Ses usages, ses enjeux, ses contraintes, Mémoire d'Ardèche et Temps Présent, No 90, 15 mai 2006, pp. 8-11.

2 - THE BALANCING WELL THROUGH POSTCARDS

|

|

|

MEURTHE-ET-MOSELLE |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption: PARROY. - Vue intérieure.

At the vanishing point of roof eaves, stands out a well sweep poised on its upright, amidst firewood piles and manure heaps. A cast-iron water pump can also be seen against the façade of the house nearest to the photographer. |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption: PARROY. - Vue intérieure

A closer view of the same well swipe. It faces the row of houses, the well being in the middle of the open yard called usoir outside one of the houses. The post is probably the work of a carpenter as evidenced by its decorative head piece and the hollow through which passes a beam weighted by a piece of wood. The hanging element comprises a wooden bar at the end of a chain. The bucket stands on the well brim. |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption: Parroy. - Un ancien Puits.

An even closer view of the same device. Its elaborate workmanship is obvious: the thickened foot of the post ends with a triangular decor on all four sides ; its head piece, carved to look like a pyramid with a rounded top, rests on a narrow stem. The axis of the beam seems to be made of wood. The wooden element weighting the beam's tail seems to be a reused piece from a former support. The hanging element comprises not just one but two bars linked to each other by a short iron chain. The parallelepiped lying to the left of the well is a drinking trough. |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption: Parroy. - Rue Chaudron.

The well sweep in the background is the twin brother of the previous one (same carved head piece on top of the post). Both devices were destroyed with the rest of the village in August 1914. |

|

|

|

BAS-RHIN |

|

|

|

|

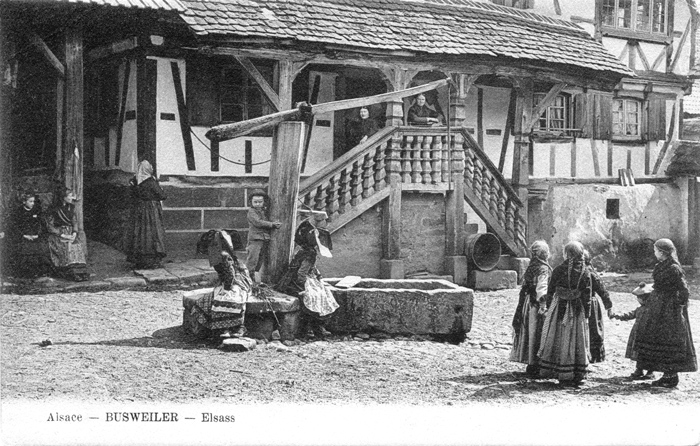

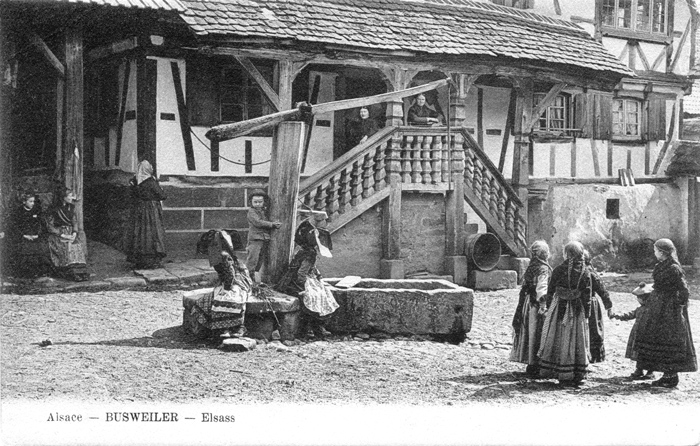

Caption: Alsace - BUSWEILER - Elsass

Caption on the back: Postkarte / Weltpostverein. Universal Postal Union

Well swipe in a farmyard in Büsweiler (in German) or Bousseviller (in French) in the Bitche region: As far as can be judged, the upright is a debarked tree trunk to the top of which are fixed two prongs for the passage of the horizontal metal shaft. A very short beam is attached to it, at the end of which hangs a wooden bar. The base of the upright is set into a large circular stone platform (reminiscent of a millstone), placed on a masonry frame: it is in fact a covered well and the device is just a hand pump, operated by means of the bar. A metal spout is fixed halfway up the hollow upright, through which the water flows into a one-piece rectangular stoone trough. The wooden board placed across the trough, under the pump spout, was used to hold the bucket while it filled up. |

|

|

|

|

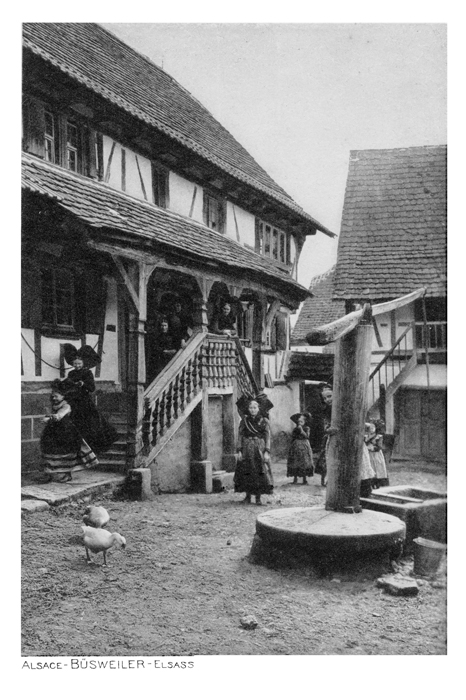

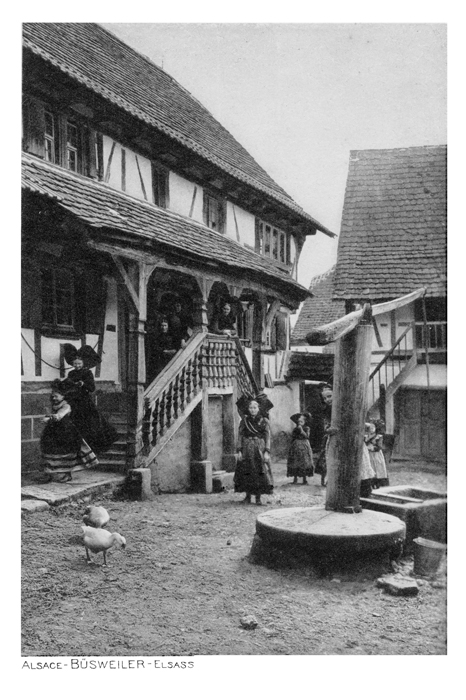

Caption: ALSACE - BÜSWEILER - ELSASS

The same device, seen from the rear. |

|

|

|

|

|

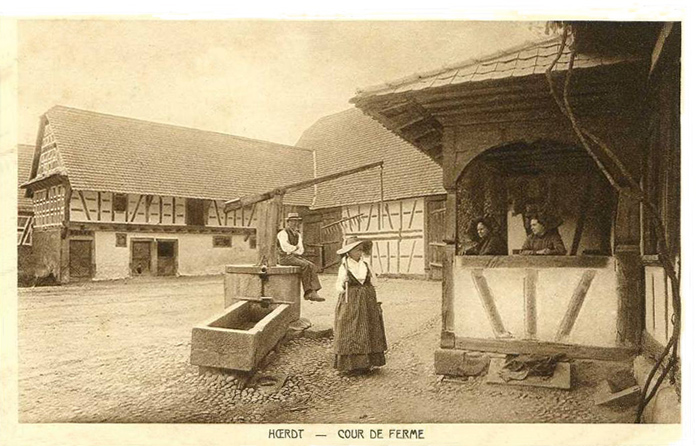

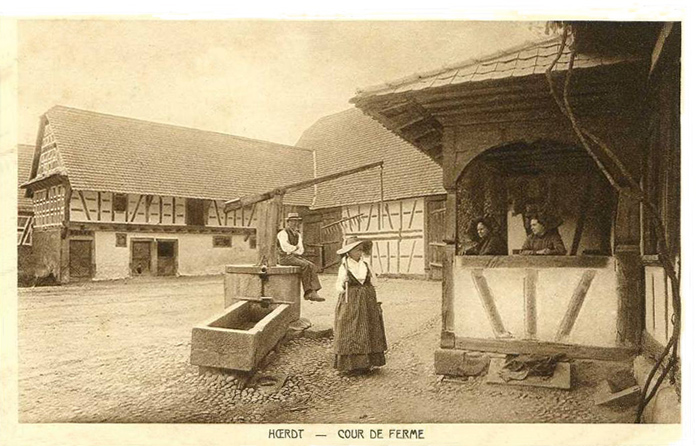

Caption: HŒRDT - COUR DE FERME

In this farmyard (in fact a former 18th century coaching inn), there is a device identical to the previous one, except that the base of the well is higher and that the flail is perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the trough. On the top of the well, in the axis of the pivot, one can see the spout through which the pumped water flows into the trough. |

|

|

|

LANDES |

|

|

|

|

Caption

on the back: Au pays landais – Vieux puits à balancier.

The legend on the back reads: "In the Landes country – Old balancing well".

With the trunk of a young tree for a post, a long perch for a beam, a metal pin running through the fork's prongs for an axis, this water sweep is a most rudimentary contraption. As the post is slightly tilted towards the well, its foot has been propped up by a couple of stays. When the machine is a standstill , the bucket hangs a few centimetres above the well's brim. |

|

|

|

|

Caption on the back: Landes - Ferme landaise et puits landais.

The legend on the back reads: "Landes. A Landaise farm and Landaise well".

A balancing well in the area round Aire-sur-Adour. The upright is a young forked tree, the flail a perch hinged on an iron pin that runs through the fork's prongs. Contrary to local rule, the bar is arched, not straight. Overall, a simple but rudimentary device, not unlike other existing Landaise well sweeps. |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption on the back: Landes - Ferme landaise et puits landais.

The legend on the back says: "Landes. A Landaise farm and Landaise well".

The post is a young forked tree, hardly thicker than the beam that hinges round a metal axis in the fork. A pail hangs from a long bar fastened by a chain to the jib. The device is at standstill, so that the pail hangs a few dozen centimetres above the well's rim. |

|

|

|

|

Caption: LANDES. - Un coin de ferme.

The upright is a forked tree, the beam is a pole hinged round a metal axis running through the fork's prongs. The hanging system – probably a bar – is barely visible. The machine is at standstill, with its jib up and its bucket hanging a score centimetres above the well's rim. Since no counterweight is visible, one can conclude that the man in the picture is holding the beam down. |

|

|

|

|

|

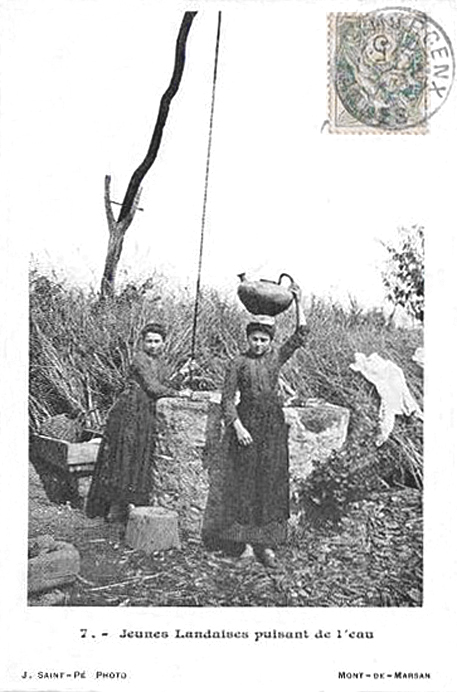

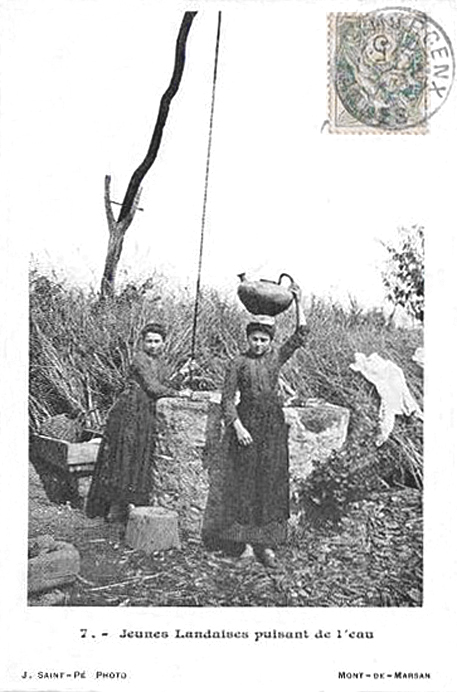

Caption: Jeunes Landaises puisant de l'eau.

Here again, the upright is a young forked trunk and the beam is a long pole which swivels on a metal axis. Only a part of the suspension system is visible: the bar followed by a chain held in both hands by one of the young female water carriers. The other girl carries a single-handled water jug or "dourne" on her head. Those were the days of the the water chore... |

|

|

|

|

|

Caption on the back: En Gascogne - Témoins silencieux du passé, le vieux puits.

The legend says:: "In Gascony - Silent witnesses of the past: the old well".

The farmer's wife, holding the bar with both hands, lowers the bucket into the well. The post is a forked tree, the beam is a thick pole weighted by a piece of wood fastened to its tail end. |

|

|

|

|

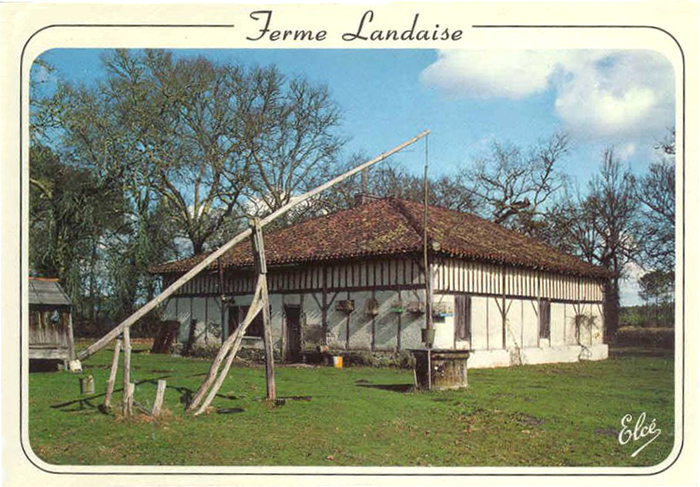

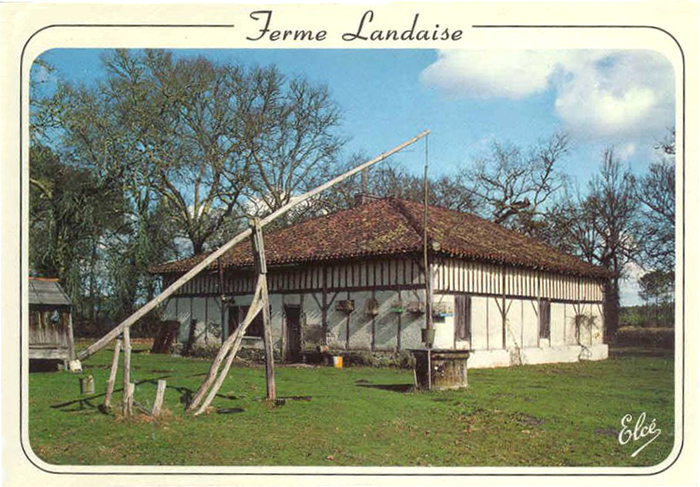

Caption: Ferme Landaise.

The upright here is no longer a forked sapling, but a slim tree trunk with two binding planks at the top through which an iron pin runs. On this is a long beam, the tail of which, weighted down with an old solid metal bucket, rests on two props (which may have replaced a portico, according to the two sectioned uprights still visible just in front). The suspension system consists of a short chain, a wooden bar and a snap hook to hang the bucket. The pivot is counterbalanced by two oblique props. |

|

|

|

SAÔNE-ET-LOIRE |

|

|

|

|

Caption: LOUHANS - Ferme Balorin The Balorin farm at Louhans, Saône-et-Loire.

While one would expect the farmer's wife to be photographed drawing water from the well, the photographer has been content with catching her simply feeding the poultry. The device is obviously the work of a carpenter : a squared post with a diamond-pointed top, a through mortise for the beam to pass, the upper part of the post strengthened by two binding pieces, etc. The beam is a tree trunk whose upper part (or jib) has been squared and made thinner. |

|

|

|

|

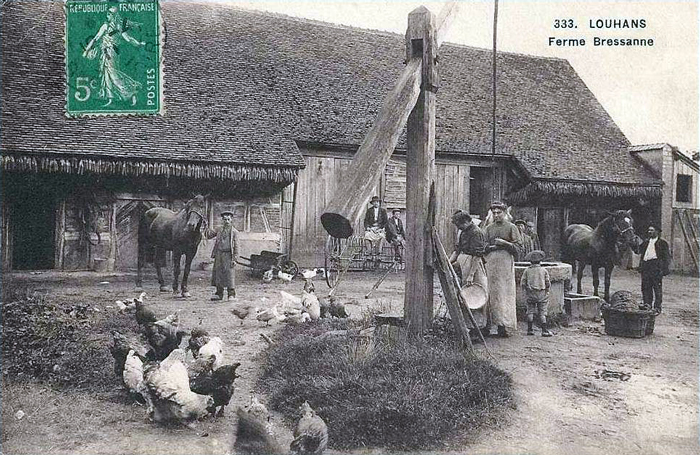

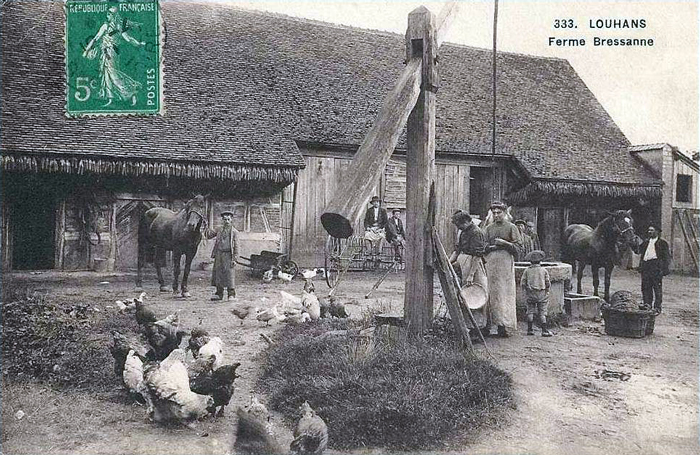

Caption: LOUHANS - Ferme Bressanne

This so-called "Bressanne farmhouse" is in fact the Balorin farm shown in the previous postcard. This time, the sweep is seen from the farmhouse's side, which is why we get a glimpse of the timber-framed barn with its ears of maize hung under the overhanging roof eaves. In this second shot, we can see the device up close, especially the unsquared tail of the beam, the through mortise, the metal axis and the bar for drawing water. |

|

|

|

INDRE-ET-LOIRE |

|

|

|

|

Caption: SAVIGNÉ-SUR-LATHAN (I.-et-L.). - Ferme de Bisse.

In this farmyard, to the left of the manor's facade, one can see a sweep held in the lowered position by one of the inhabitants (it is the tail, recognisable by the ballast it carries, that is raised). The pivot is straight and not slanted, and is finished with a fork-like substitute made of two binding pieces. |

|

|

|

CHARENTE |

|

|

|

|

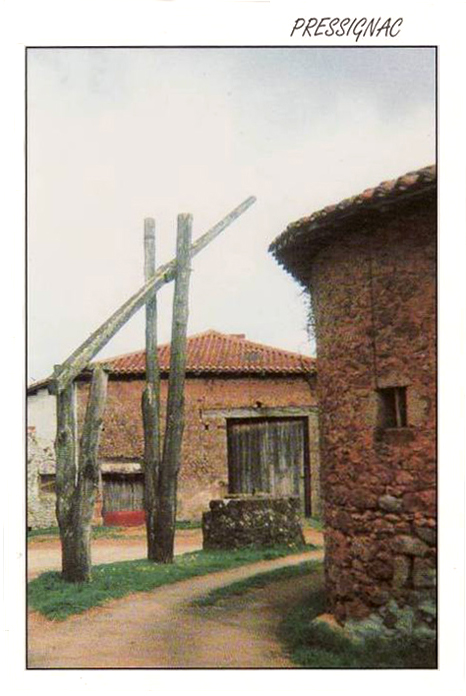

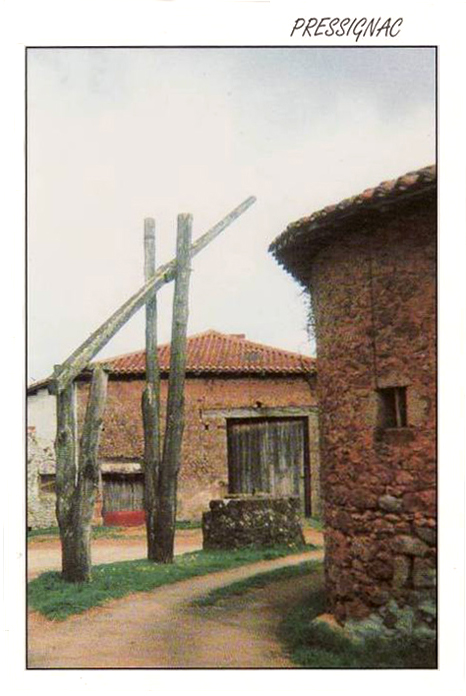

Caption: PRESSIGNAC

The pivot of this impressive machine, located at Pers, is made up of two diverging vertical branches from the same trunk, all left unfinished. The flail is articulated on a metal axis which crosses the top of the two branches. The tail, which is squared off, rests on a support of the same origin and configuration, but with a wooden crosspiece joining the tops of the two branches. The poor photographic quality of the document does not allow the suspension element to be distinguished. |

|

|

|

VIENNE |

|

|

|

|

Caption: St-SAUVANT (Vienne). - L'Eglise

A particular feature of this machine is its post heavily tilted in the direction opposite the well, resulting in its flail being almost perpendicular to the ground. The upright is a thick squared post ending with a fork-like mortise in which the beam – also squared – swivels. The length of the bar for drawing water is an indication of the depth of the aquifer. |

|

|

|

HAUTE-VIENNE |

|

|

|

|

Caption: SAINT-JUNIEN - Une Ferme à Rieubargy et Puits

The caption seems truncated: it should read "Une ferme à Rieubarby et Puits à balancier".

The device is quite an impressive sight judging from the diameter of the upright and that of the forked post which serves as a stop for the beam. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caption: Vicq-sur-Breuilh (Haute-Vienne).

The vertical component of this powerful contraption is a roughly squared tree trunk whose top has a U-shaped mortise. A robust beam made out of a tapered tree trunk rotates round a metal axis. A rope is fastened to the tip of the jib. The area round the well is protected by wire fencing. |

|

|

|

CÔTES-D'ARMOR |

|

|

|

|

Caption: BRETAGNE (Collection E. Hamonic, St-B.) - Puits à balancier et abreuvoir (Environs de St-Brieuc).

This Côtes-d'Armor well swipe is in a different league from its counterparts in the Landes region, judging from the diameter of its upright and the squaring of its beam. The force arm is weighted by an iron cauldron fastened to its lower end. The hanging element seems to have no wooden bar, only a chain (a sure way to avoid splinters...). The foot of the upright is buttressed by three stays. The opening of the well is amazingly narrow. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

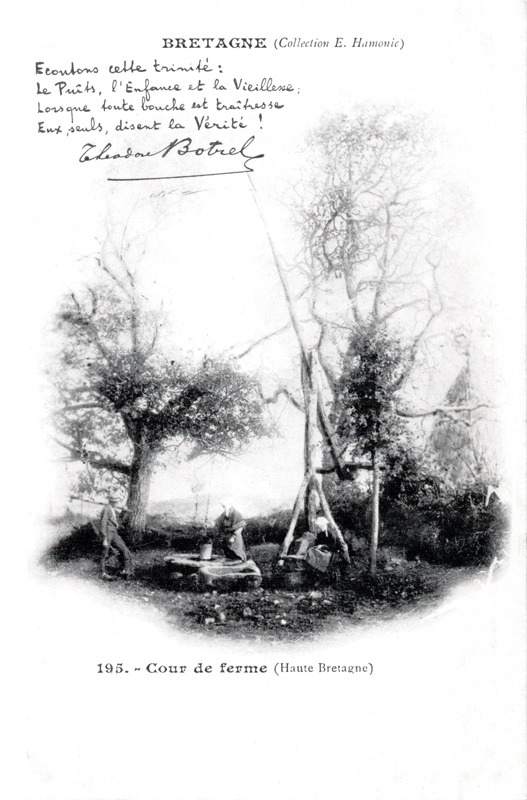

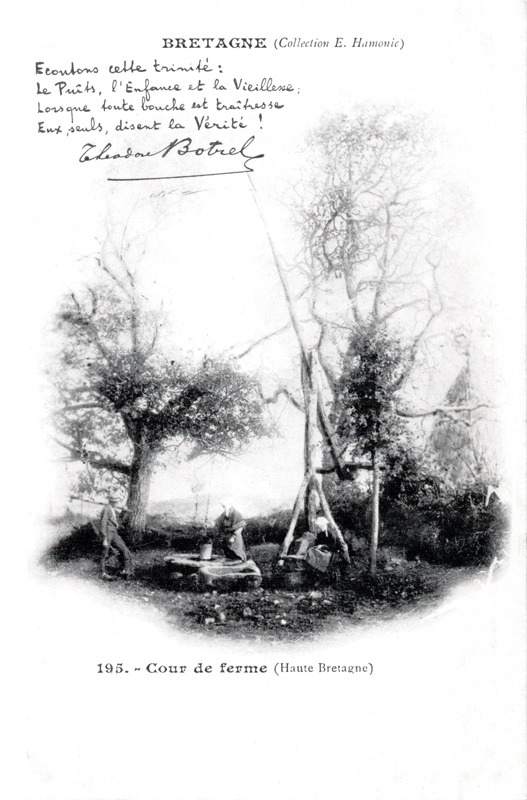

Légende : BRETAGNE (Collection E. Hamonic, St-B.) - 195. - Cour de ferme (Haute Bretagne).

Fortunately, in another postcard published by E. Hamonic, the lifting apparatus is fully exposed. The upright is a forked tree trunk and the beam swivels between the prongs. The force arm is weighted by an iron cauldron plus a wooden log. the upper end of the beam culminates at 8 to 10 metres high. Because of the photo's poor quality, little more can be said. |

|

|

|

3 - REVIEWS PUBLISHED IN THE JOURNAL L'ARCHITECTURE VERNACULAIRE

ROUVIERE Michel, Les balanciers de puits ou « manlèves » du bas Vivarais, in Revue des enfants et amis de Villeneuve-de-Berg, 1990, pp. 18-27 (review by Christian Lassure, in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 14, 1990, p. 68).

In this article, Michel Rouvière points out that a number of swipes for drawing water are still standing in the commune of the Assions in the Ardèche département. In their design and

structure, these swipes are identical to those encountered in other French regions. Their metal parts come from salvaging. Water is drawn either from garden wells whose water originates from a nearby stream or from tanks whose water comes from a spring or even a river. The manlèves, as they are called, come with a number of small hydraulic devices used for recouperating, channelling, storing and heating water for irrigation: grooves and circular

basins (or gourgues). The watering technique consists of splashing water with an espoucho, i.e. an old saucepan tied to the end of a long handle.

At a time when water becomes scarce in Southern France, the manlèves of lower Ardèche deserve our whole attention.

BARBIER Jean-Marie, Les puits à balancier de Meurthe-et-Moselle, in Cartes postales et collection, 1990, No 132, pp. 16-21 (review by Guy Oliver in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 19, 1995, p. 96).

The author stresses the vital role of water and the high level of expenses that is incurred by a small, unaffluent commune in order to supply its inhabitants with water. He evokes the principle of the ancient Egyptians' shaduf, a forerunner of the well swipe that was widely used in Lorraine until the early 20th century.

This short article contains a facsimile of an October 26th, 1750 estimate for the refurbishment of three communal wells in Mouacourt as well as a 1782 estimate (taken from P.

Simonin's book, Le puits à balancier lorrain, 1984) about a well in Pont-Mousson.

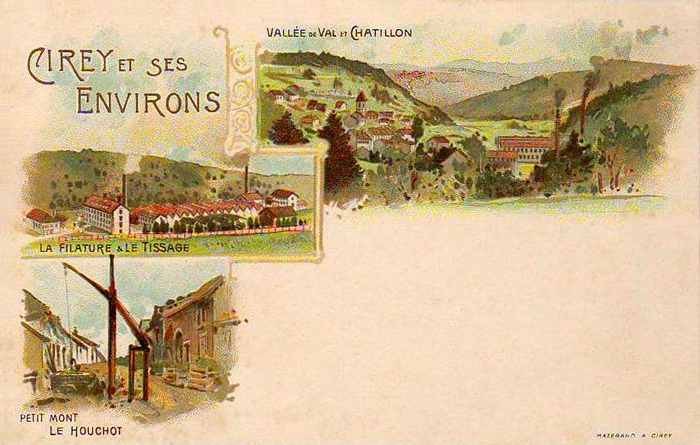

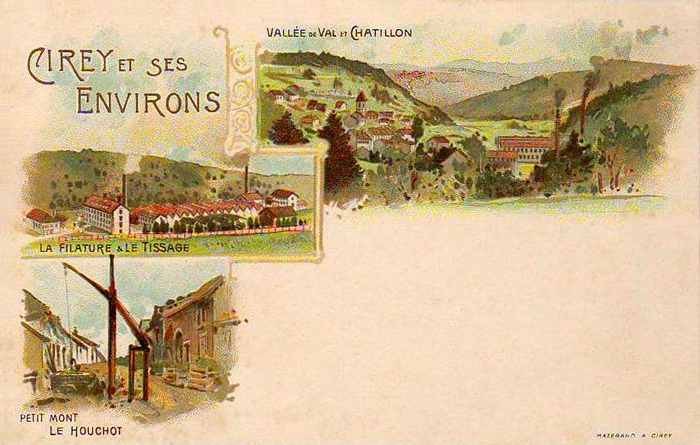

The interest of the article lies in its seven early 20th-century postcards showing balancing wells that supplied water to homes in Lorraine: Parroy (3 pictures), Petit-Mont (2 pictures), Mouacourt and Ogévilliers. These pictures bring out the many similarities of the four devices.

|

|

|

Caption: CIREY ET SES ENVIRONS

In this multiview postcard of Cirey and its surroundings, one of the landscape watercolours reproduced shows a superb swipe at a place called Le Houchot in Petit Mont (Petitmont), a village in Meurthe-et-Moselle. The top of the upright is clearly carved and the tail of the beam rests on a robust portico, but little more can be said. |

| |

|

|

|

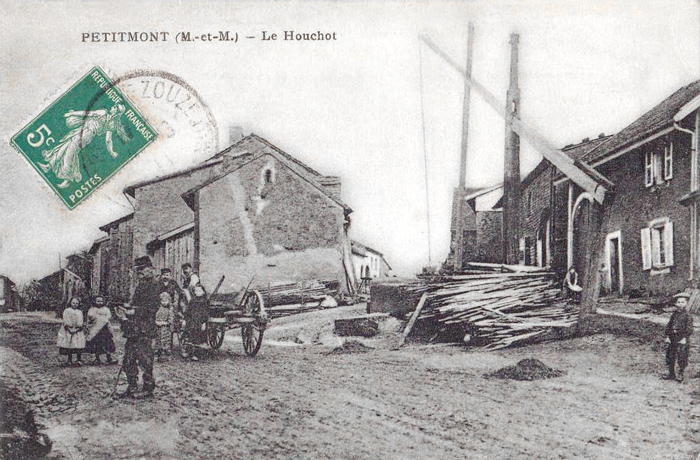

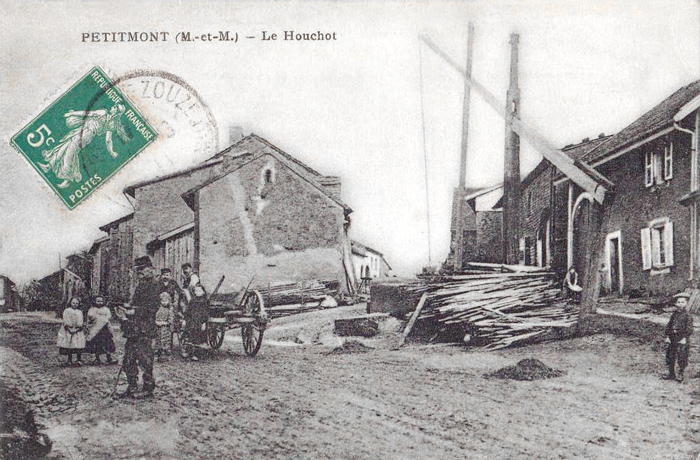

Caption : PETITMONT (M.-et-M.) - Le Houchot.

This close-up view of Petitmont's machine gives more information about it. The pivot is a squared-off trunk, with a long through mortise at the top to accommodate the wide oscillations of the beam on its transverse metal shaft. The tail of the beam rests on the top of a post set in the ground (and no longer a portico as in the previous card). A rare ornamental fantasy, the upright is extended above the mortise by a lightened part crowned with a faceted cabochon. The machine is in the resting position, the bucket attached to the suspension element is placed on the rim of the well. A long pole is erected between the upright and the end of the jib

presumably as a sort of guide for the movement of the flail. |

Once more, old postcards, although often neglected or simply ignored, constitute an irreplaceable source of information.

To print, use landscape mode

© CERAV

January 18th, 2006 - Augmented on February 1st, 2008 - October 3rd, 2021

The above contribution will be referred to as:

Christian Lassure

The balancing well in France

http://www.pierreseche.com/balancing_well.htm

January 18th, 2008

page d'accueil

sommaire architecture vernaculaire

|