Nat AlcockTHE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CRUCK CONSTRUCTION AT NÉCHIN, BELGIUM

Abstract The eighteenth century barn of the farm at Néchin described here has proved to be of exceptional significance in both a regional and European context. It contains timbers of cruck form, the only examples known to survive in Belgium or northern France (although a few were recorded there before the Second World War). Thus it is the unique example confirming the existence of this historic structural technique in the region. Crucks are widely distributed in Britain (mainly medieval in date), but are extremely rare in continental Europe. The date of the present structure has yet to be determined, in particular whether the crucks were re-used from an earlier building, or whether they were newly made for the barn, which would indicate knowledge of cruck construction in the region (as is suggested by the structural analysis).

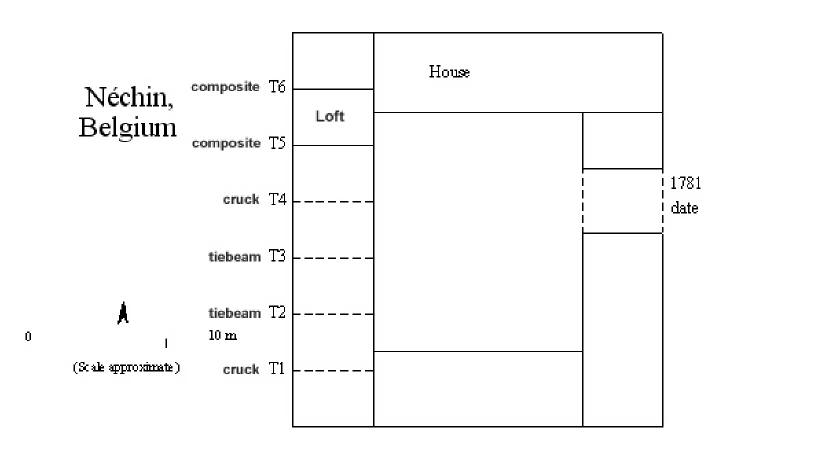

Introduction This farm at Néchin, situated about 10 km north-west of Tournai, Belgium, was visited on 1st May 2006. It proved to be of exceptional interest and significance, and this memorandum summarises the observations made. The photographic illustrations were in part taken during this visit (NWA), in part taken before and during the renovation of the house 15 years ago (P. Dormal). Overall layout This farm consists of a quadrangle of buildings, all similar in appearance, constructed in 18th-19th century brickwork, roofed in tiles (Fig.1). Of the four ranges, the house itself stands on the north side and the barn that is the particular subject of the present examination is on the west side. The gateway in the east range, opening to the road, carries the date 1781, but the complex had the same form before this, since a quadrangle is shown on a detailed map of 1771-6 (inf. P. Dormal).

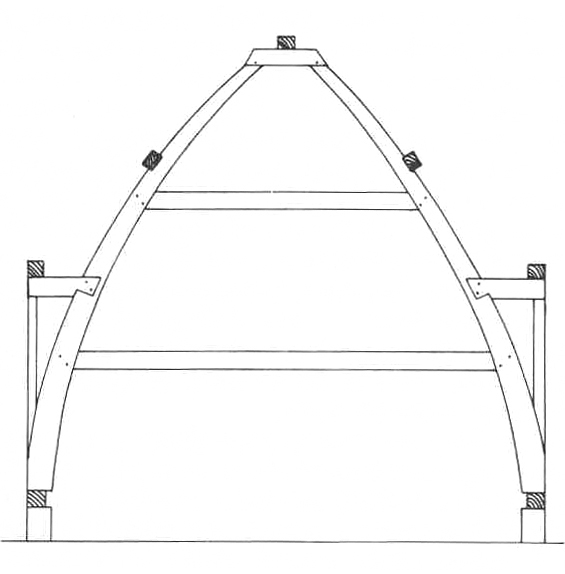

Roof structure The north, east and south ranges have (or had before modernisation) roofs of standard Belgian form; the house (north) range has tiebeams secured by anchor ties, that carried bearer trusses with short principals supporting collars. However, the barn that comprises the west range is entirely different and of exceptional significance. It has a span of 4.83m between the brick walls and contains six roof trusses. Surprisingly, these have three different forms. Trusses T1 and T4 are full cruck trusses; T2 and T3 are tiebeam trusses, while T5 and T6 have posts and principals, jointed with clasping stub tiebeams; in the pre-restoration photographs, these apparently stand on tiebeams supporting a loft. The cruck trusses Cruck truss T4 is shown as it was before restoration in Fig. 3, and as at present in Fig. 4. The blades are well-curved and cross at the apex, where they hold the ridge piece; they seem to be cut from individual trees. Truss T1 is similar (Fig. 5), though here the blades are apparently halved (made from a single tree sawn down the centre), and it is notable that they are very white in appearance; the wood from which they are made is not immediately identifiable, but the appearance suggests that it is not oak. This truss stands in a part of the barn that has not been modernised; it was originally open from floor to roof, but a concrete floor has been inserted (20th century?); a part wall divides the barn on the line of T2 (since fully infilled). Fig. 6 shows T3, this wall, and truss T1 beyond it.

Neither cruck truss has any substantial timber spur linking it to the wall-head, though both have light nailed-on spurs (visible on Figs 3a-b and 5b). These appear to be relatively recent additions. The apex joints are held by two pegs, and the collars sometimes by one peg, sometimes by two. The collars project beyond the line of the blades, where they carried the original purlins (replaced during restoration); blocks of wood appear to have kept the purlins in place (Fig. 3a).

Interpretation The form of the cruck trusses, T1 and T4, in particular the absence of any spurs strongly imply that they relate to solid walls, e.g. of brick, rather than walls of timber-framing (contrast the spurs connecting the cruck blades to the walls in a typical English truss with timber-framed walls, fig. 7). An initial reaction to the surprising mix of different types of truss, two with crucks, two with tiebeams and two with composite frames, is that the crucks were re-used from an earlier building. However, an alternative interpretation is that the different types of truss were chosen specifically to perform different functions within the existing building. The two cruck trusses span spaces fully open to the roof. The two trusses with tiebeams are supported on brick pillars that define the barn doorways. Finally, the two composite trusses were used above beams supporting a loft.

These alternatives have different implications for the dating and context of the cruck trusses, but in both cases, the trusses have exceptional significance with important implications for the use of cruck construction in Flanders and northern France. Significance Cruck construction is a medieval carpentry technique, best known in the British Isles, where some 4,000 examples have been recorded (Alcock, 1981 and later information). The earliest examples date to the 13th century, and they are among the first standing timber buildings existing in England. Examples of the technique have been reported from continental Europe, though they are very limited in number (perhaps 50 recorded overall), widely distributed from Flanders to the Dordogne, Brittany to Bulgaria (Meirion-Jones, 1981). It remains an unresolved problem, whether their distribution is the result of diffusion, or whether the technique was invented independently in different places. Cruck construction in Flanders A number of 13th century roofs in Flanders show such close relationships to structures in England with affinities to cruck construction (‘base-crucks’), that it is considered highly likely that one form is derived from the other, although the direction of movement is uncertain (Hoffsummer, 2002, 192). However, in Flanders, these roof timbers are set on stone walls and do not closely resemble true cruck trusses; they develop into the classic Flemish ‘bearer’ truss that is widely distributed in the Low Countries (ibid. 249ff.). More than 70 years ago, a few authentic cruck structures were reported from coastal Flanders (Alveringem, Ramskapelle, Westkapelle) (Trefois, 1937; Meirion-Jones, 1981), but their continued survival since then has not been established. These crucks had timber-framed walls and blades meeting on a king-post standing on the collar, rather than crossing as at Néchin. Both forms of apex are found in England, where they are classified as type G- and D-apexes, respectively (Alcock, 1981); G-apexes are rare, with only 29 examples recorded, while 179 examples of type D are known. At present, the only true cruck structure known to survive in Belgium or northern France is that at Néchin described in this memorandum. Thus it is of exceptional significance as the unique example confirming the existence of this historic structural technique in the region. Its fuller significance will only become clear with further work, and in particular the establishment of its date through dendrochronology. Its relationship to local carpentry traditions depends particularly on which of the alternative interpretations is correct. 1. If the crucks are reused from an earlier structure, they indicate the presence of a tradition using crucks that was probably extinct by the later 18th century. 2. If, on the alternative interpretation, the crucks were newly made for the existing building, they indicate knowledge of the technique in the region up to 1780-1800, with the local carpenters able to select this as one design among several, according to the specific function of the roof truss. In both cases, it seems that the technique had been developed from timber-framed prototypes to its use with brick walls, a change that never took place in England. The final question that further research might answer is the initial date of adoption of cruck construction in the region. Is it possible that it was imported in the 16th century, during the brief period of English overlordship, as has been suggested as a possibility in the Limousin, France (Bans & Bans, 1979) ? BIBLIOGRAPHY N. W. Alcock, 1981, Cruck Construction: an Introduction and Catalogue, Council for British Archaeology (see http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/library/cba/rr42.cfm) J.-C. Bans & P. Bans, 1979, ‘Notes on the cruck truss in Limousin’, in Vernacular Architecture, 10, 22-29. P. Hoffsummer and others, 2002, Les charpentes du XIe au XIXe siècle: Typologie et évolution en France du Nord et en Belgique. G. Meirion-Jones, 1981, ‘Cruck construction; the European Evidence’, in Alcock, 1981, 39-56. A. V. Trefois, 1937, ‘La technique de la construction rurale en bois’, in Folk, 1, 55-72. © Nat Alcock - CERAV To be referenced as : Nat Alcock The author: French version bilingual version sommaire tome 34-35 (2010-2011) sommaire site architecture vernaculaire |